The Violent, Shocking Children’s Tale of Chirin no Suzu

“In order for some to live, others must die.”

When tackling ideas of subversion and unconventional narratives in anime, it’s easy to be reminded of seminal bait-and-switch series along the lines of Neon Genesis Evangelion and Mahou Shoujo Madoka Magica. Shows that disregard the norms of ‘conventional’ storytelling by playing into the viewer’s presumptions about narrative are often thought of as a distinct product of a modern culture where audiences are numb to seeing the same repetitious narrative tropes trotted out on screen where no surprise or shock is to be witnessed at all. But some of you may be surprised to hear that this kind of narrative subversion has come in waves over the years, with one enduring example dating back to 1973, with Chirin no Suzu (or ‘Ringing Bell’).

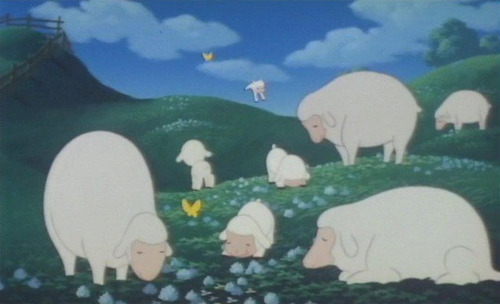

Clocking in at a mere 47 minutes long, Chirin no Suzu is largely obscure outside of Japan (despite having an English-dubbed VHS release), but regarded as an influential hidden gem of the ‘70s. The plot revolves around a sprightly little lamb named Chirin who lives on a picturesque farm in the countryside with a herd of other sheep. Chirin’s youthful curiosity mixed with his clumsiness has prompted his mother to tie a bell around his neck that rings wherever he goes, so that if he gets lost, she can always find him. The naive young lamb wanders outside of the farm one day, much to his mother’s shock, who imparts a warning about all the dangers that could face him beyond the fence. Chirin and his mother then return to their idyllic life in the rolling, pastoral countryside. Seems innocent enough, right?

Wrong.

The story instantly shifts into a brooding revenge story as a wolf breaks into the sheep’s barn during the night and slays Chirin’s mother as she tries to save her son. The young lamb is traumatised by the event, and vows to exact retribution on the wolf who killed his mother. At this point, Chirin is still a weak lamb who can’t even kill a mouse, let alone a wolf. This drives Chirin to follow his mother’s killer across the most treacherous parts of the countryside, learning how to hunt and fight like a heartless killer, in the hopes that one day he will be strong enough to viciously take down the wolf that killed his mother. Over the course of the film we watch Chirin’s growth (or decline?) from an innocent young lamb to a tough, emotionally-guarded ram, and without giving too much away, the resolution is less than cheerful.

The dark, oppressive atmosphere looming over the entire film, coupled with the bizarre, dysfunctional relationship between Chirin and the wolf is enough to bring even the hardest viewers down to dreary despair. But what’s arguably most shocking thing about Chirin no Suzu is the studio behind it, which is none other than Sanrio. Yep, the same company that spawned Hello Kitty and more insurmountably-large platters of sickeningly-saccharine kid-friendly kawaii produced an anime about a baby lamb exacting revenge on their mother’s killer and developing a brotherly relationship with them in the process. What’s even more bizarre is its G-rating. It’s not a particularly graphic film in its depiction of violence, but the content alone is enough to make damn sure I’m never letting this film near any children.

Either way, there’s a lot of narrative elements to be appreciated by a more mature audience, and some interesting trivia surrounding the film, too. Takashi Yanase, writer of the book the film was originally based off, was a former colleague of the venerable Osamu Tezuka, and this adaption was released in the same year as the animated adaptation of Richard Adams’ Watership Down, another story featuring cute farm animals, violent deaths, and crushing, soul-rending despair (and most likely the reason an English dub of Chirin was released outside of Japan). Chirin no Suzu is a nice little treasure sealed in the tomb of mostly-forgettable ‘70s anime. It doesn’t exactly stand strongly on its own two feet against modern giants that are no strangers to showing violence and gore on primetime television, but watching it with context in mind rewards you with a classic marvel of subversive storytelling, and 47 minutes of existential questioning that would make Albert Camus blush. The only issue? You may need counselling afterwards.

- The Violent, Shocking Children’s Tale of Chirin no Suzu - June 3, 2015

- Seven of the Most Challenging Osu! Beatmaps - January 20, 2015

- Four Underrated Japanese Games - December 22, 2014